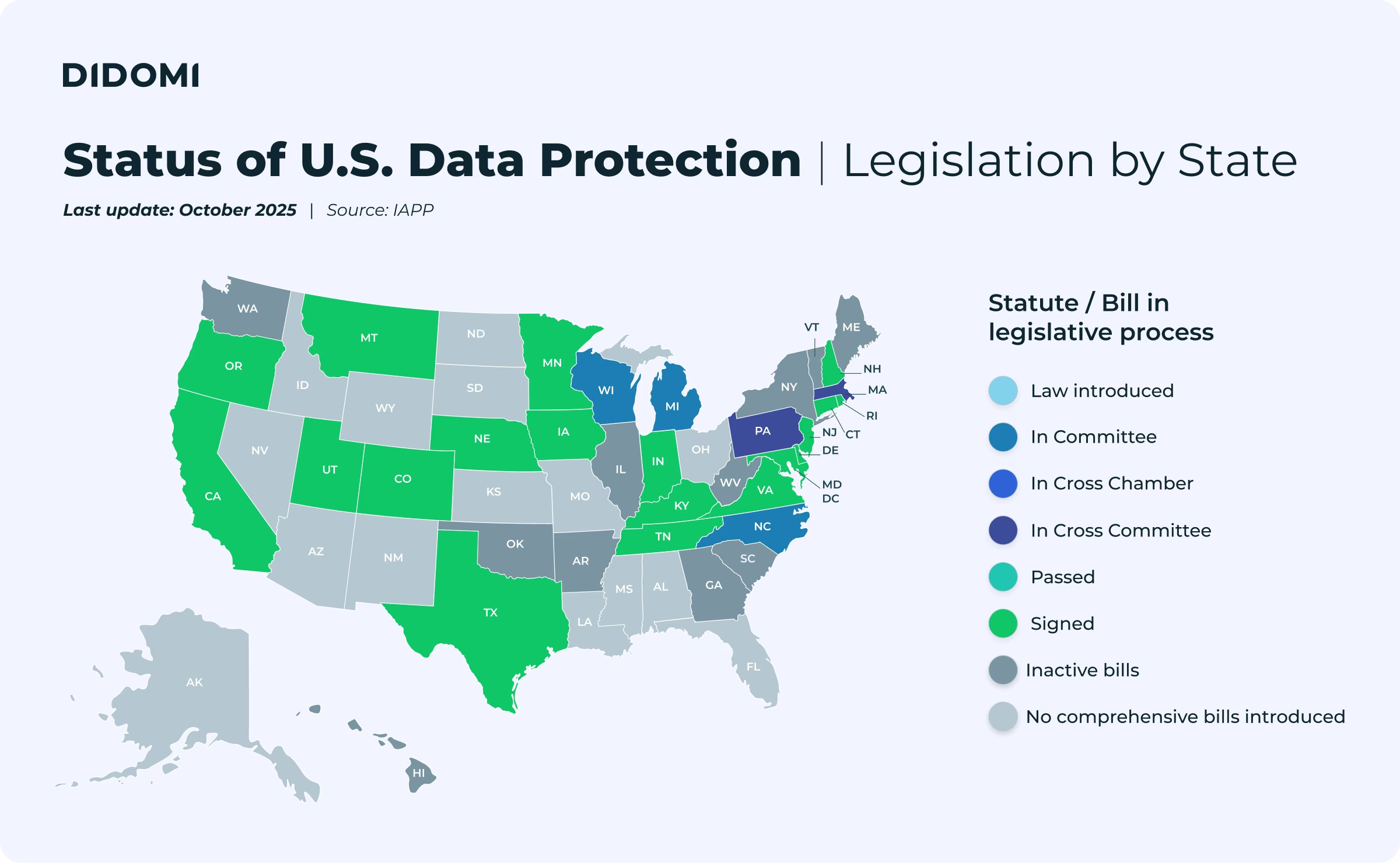

Nineteen U.S. states enacted comprehensive consumer privacy laws between 2018 and 2024. In 2025, data privacy laws in eight additional states will come into effect. By the end of 2025, around 150 million Americans—nearly half the U.S. population—will be covered by a state-level privacy law.

Keeping up with this growing regulatory patchwork of expanding state laws presents a significant compliance challenge for businesses, but until now, it has been made easier by the relative uniformity of these laws and the often-overlapping obligations they place on companies

But that is beginning to change. Several years into the data privacy revolution that is sweeping through states, legislatures are taking more novel approaches to protecting personal data. This means that, increasingly, a “one-size-fits-all” or even a “one-size-fits-most” approach to compliance won’t be enough.

Sensitive personal information is an area of privacy law that has seen states move in different directions. As states expand their definitions of sensitive data and introduce heightened protections for it, businesses should be prepared to make corresponding changes to their compliance strategies to avoid penalties, legal liabilities, and loss of consumer trust.

What Is sensitive personal information?

Five states (Iowa, Delaware, Nebraska, New Hampshire, and New Jersey) have privacy laws going into effect in January 2025, with three additional states (Tennessee, Minnesota, and Maryland) joining them later in the year, bringing the total number of states covered by comprehensive privacy laws up to 27—and counting—by October 1, 2025.

While there are many substantive differences among these state privacy laws, one fundamental principle they share is the recognition that some types of personal data pose heightened risks to individuals if lost, stolen, or disclosed without authorization—and therefore require additional protections to keep it safe. This data is known as sensitive data, or sensitive personal information.

Not all personal data is treated equally in state privacy laws

The breadth of what is considered “sensitive personal data” differs significantly from state-to-state.

IAPP notes in a 2023 report that all states define sensitive data to include information about race or ethnic origin, religious beliefs, genetic data, biometric data, health data, and sexual orientation, and that most include precise geolocation data.

Many states, including Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Indiana, Iowa, Montana, Oregon, Tennessee, and Virginia, categorize “personal data from a known child” as sensitive data. And California has added categories such as a consumer’s philosophical beliefs and the contents of their mail, email, and text messages to their definition of sensitive data.

Although the California Consumer Privacy Act (CCPA), the first state comprehensive privacy law in the U.S. and generally considered to be the most consumer-friendly of the laws passed to date, did not initially address sensitive data, this was updated with amendments from the California Privacy Rights Act (CPRA), including the right of consumers to limit the use and disclosure of sensitive personal information. The CPRA made California the first U.S. state whose privacy law addressed the concept of “sensitive personal information.”

California has largely followed its own approach to consumer privacy law. The other states, initially at least, generally based their laws on the Washington Privacy Act (WPA), a bill that has yet to pass but serves as a model framework for privacy legislation in other states and is the basis of eighteen of the nineteen state comprehensive privacy laws enacted to date.

States that modeled their privacy laws on the Washington bill have incorporated strong, privacy-protective elements from the California model, but the CCPA and WPA frameworks have some high-level differences, including in how they treat sensitive data.

- WPA/Opt-in: Most states, following the WPA framework, use an opt-in model for sensitive data that bars businesses from collecting and processing sensitive data unless a consumer opts-in to that processing by providing explicit consent (i.e., through the use of a dedicated consent form). In all states except for California, Iowa and Utah, consumers must opt in before a business processes their sensitive data.

- CCPA/Opt-out: The CCPA framework is an opt-out regime with respect to sensitive data processing, meaning that businesses can process sensitive data unless a consumer actively chooses to opt out of processing using a link on their homepage.

Use the following visual for a summary of sensitive personal information under the various U.S. state laws:

{{us-spi}}

The expanding scope of sensitive personal information

California is not the only state that uses an opt-out approach to sensitive data processing. But it is unique in that it is the only state that gives consumers the right to limit the use and disclosure of sensitive personal information.

Under the CCPA approach, individuals can direct a business to limit its use of sensitive personal information “to that use which is necessary to perform the services or provide the goods reasonably expected by an average consumer who requests those goods or services,” to perform certain “business purposes” under the statute, and as authorized in the regulations.

California has long been ahead of the curve in terms of legislating U.S. privacy rights. Not only was it the first state with a comprehensive privacy law addressing the concept of sensitive personal information, but its definition stands apart from subsequently passed laws by incorporating more European-inspired elements than other U.S. laws, such as personal information about philosophical beliefs and union membership.

But as we approach the decade anniversary of the CCPA’s enactment and the number of states with comprehensive data privacy laws expands, the definition of “sensitive data” is expanding as well. Some notable trends that have emerged in this area, according to a 2024 report from the Future of Privacy Forum (FPF), are:

- State definitions of health data have evolved, expanding coverage beyond diagnosis to cover conditions and treatments.

- States have added a new category of sensitive data: “status as victim of a crime.”

- Colorado and California have amended their laws to add neural data as a category of sensitive data.

- A handful of states now consider data revealing status as transgender or non-binary to be sensitive.

- Several states have expanded the definition of biometric data to include data that can be used for identification purposes (and not just data that is used for such purposes).

Examples of states that have branched off in different directions in how they define sensitive personal information are Texas, Oregon, Delaware, and New Jersey.

- The Texas Data Privacy and Security Act added information relating to an individual’s “sexuality” as sensitive data instead of their “sexual orientation,” potentially establishing broader protections for this category than other states.

- Oregon expanded the definition of “sensitive” data when it added categories like “status as transgender or nonbinary” and “status as victim of a crime.”

- Delaware was the first state to include “pregnancy” as a category of sensitive data within the broader category of “mental or physical health condition or diagnosis” data that more states are adopting.

- New Jersey added mental or physical health “treatment” to its definition of sensitive data, which also includes a mental or physical “condition or diagnosis.”

Other states that have been first movers in establishing more expansive definitions of sensitive data are Connecticut (consumer health data), Colorado (citizenship), and Utah (medical history).

Moving forward, state definitions of “sensitive” personal information will likely only continue to expand. Here are just a few developments to monitor:

- California is amending the CCPA by adding information about children under the age of 16 to its definition of sensitive personal data.

- Colorado, responding to advancements in brain scanning and interface technologies, has passed a bill that adds “biological data” to the Colorado Privacy Act’s definition of sensitive data, creating a carveout for “neural data” that covers activity of the human brain and nervous system.

- Maine is considering privacy legislation that would use a definition of “sensitive data” that covers information like private photos and recordings and video viewing records.

FPF provides this resource for how sensitive data is defined under various state privacy laws. It is illustrative of how fractured and expansive the concept of “sensitive data” is becoming.

Even among states that have relatively similar laws on the books, there are minutiae that set them apart. Consider the category of “precise geolocation data,” for instance. More than a dozen states define this to mean geolocation data with a radius of ≤ 1,750 feet, but California is an outlier in defining it as ≤1,850 feet. Then there’s Minnesota, which defines it as geographic coordinates with an accuracy of more than three decimal degrees of latitude and longitude.

On a meta level, the broadening definition of sensitive data raises a fundamental question that policymakers may be forced to address in subsequent legislation. Professor Daniel Solove argues in a recent paper that “[i]n the age of Big Data, powerful machine learning algorithms facilitate inferences about sensitive data from nonsensitive data. As a result, nearly all personal data can be sensitive, and thus the sensitive data categories can swallow up everything.”

Expanding definitions, expanding protections

Not only do states differ in how they define sensitive data, but they also afford varying protections to this special category of personal information.

As noted, in the opt-out regimes of California, Iowa, and Utah, consumers must be given the opportunity to opt out of the processing of their sensitive data—but only California gives consumers the right to tell businesses to “limit the use or disclosure” of sensitive data that is used to infer characteristics about them, a nuance that places additional compliance burdens on businesses that handle this data.

To take another example from just one state, the expanded definition of sensitive data in the CTDPA to cover “consumer health data” prevents regulated businesses from:

- Selling or offering to sell consumer health data without obtaining opt-in consent.

- Providing employees or contractors with access to consumer health data unless the recipient is subject to a statutory or contractual duty of confidentiality;

- Providing processors with consumer health data unless the contractor is bound by the contract required under the CTDPA; or

- Geofencing mental, reproductive, or sexual health facilities, within a boundary of 1,750 feet, for identifying, tracking, or collecting data or sending notifications to an individual about their consumer health data.

The majority of states, because they are “opt-in” states for sensitive information processing, place the onus on covered entities to obtain freely given, specific, informed, and unambiguous consent in order to collect and process consumers’ sensitive personal data.

Many state laws additionally require covered entities to complete a data protection impact assessment regarding their processing of sensitive data.

How Didomi can help companies comply with sensitive data requirements

IAPP writes in its 2024 U.S. State Comprehensive Privacy Laws Report that, up until this year, comprehensive privacy legislation was relatively uniform, with marginal differences in areas like jurisdictional thresholds and definitions of sensitive personal data. However, says IAPP, the new privacy laws being passed introduce provisions “meant to address privacy harms in unique ways that present new compliance challenges.”

Now more than ever, the devil is in the details for businesses subject to state privacy laws. In this changing legal ecosystem, a strategy that focuses on making only minor adjustments to an existing compliance strategy could come up short, exposing companies to fines and reputational harm.

Using solutions from Didomi, such as multi-regulation consent management, privacy requests, and compliance monitoring, you can capture consent to use sensitive data and stay compliant across global regulations, devices, and domains, both online and offline.

Data privacy compliance and a great user experience are two sides of the same coin for businesses adapting to today’s privacy-first environment. Contact the Didomi team to request a demo and learn more about how Didomi helps companies put customers in control of their data, generating trust, privacy-conscious growth—and ultimately, revenue.

{{us-map-link}}

.svg)

.jpeg)

-%20Everything%20you%20need%20to%20know.avif)

.avif)